Roughly 70% of the earth’s landmass is located above the equator. That means, less than one third of the earth-on-earth is below, south of the equator. With Africa and Australia so far away, the narrow tip of South America is like the end of a diving board over a huge pool. Ushuaia is at the end of that diving board with its toes over the end. Calendar wise, winter was still a week away but snow on the mountain was there for good. Even though snow melted on streets and sidewalks, it was in the air all the time.

Los Cormoranes in Spanish; in English we know Cormorants as big, black diving birds. Most commonly seen basking in the sun with their wings spread, they were the name sake for our hostel. The main building was a two-story on the corner at the top of a steep hill. An office was just inside the door and a stairway up to the study. French double doors on the right opened up into the commons area with lounge, kitchen and dining room. At the far end was another set of double doors leading outside. A narrow grass strip was flanked by private rooms on the left and a bank of elevated dorms and community showers and bath room on the right. Waking up there was pleasant with daylight spilling in the window plus something I couldn’t put my finger on. When my feet hit the floor I knew; the polished concrete floor was warm and I was surprised by how good that felt. Hot water heat in the floor made up for the steep climb.

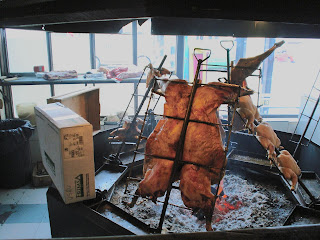

On the bus ride the day before, there were four coeds across the isle, speaking French. In the last half hour before we reached our destination, one of them noticed my guitar and asked in Spanish, “Tocas?” Did I play. In my best Español I replied, “Sí pero solo un poco.” Her eyebrows shot up and she blurted out, “Oh my God, you speak English.” My gringo accent was too bold to suppress. It started a round robin conversation that lasted the rest of the ride. They were students from Montreal, figured this trip was a good time to practice their French. On the bus platform we decided to meet the next day. They were going on a Beagle Channel boat tour and wanted me to go along. So I had something to do the next morning. After the continental breakfast I went down to the booking office; the tour price was reasonable and I was invited so I reserved my ticket and went for a walk on San Martin Ave. La Rueda is a buffet restaurant out on the east end of the Avenue. It is a parrilla, a grill where they cook on an elevated, open hearth with chickens, sheep, beef splayed on steel rods over the coals. All you could eat for $7.50 American; I would become a regular. You take your plate up to the grill master, tell him what you want. With a cleaver and saw he carved out what he thought you could manage and you dragged it back to your table like a Neanderthal. Their salad bar was a lazy suzan with some veggies, jello and cottage cheese. Not that it wasn’t good, just that veggies in Patagonia are little more than garnish. They kept restocking bread and potatoes but I was the only lettuce and carrots person there.

I made the boat tour with time to spare. Only a dozen or so tourists, the captain slipped into and out of Spanish, German and English leaving us to patch together and share anything we made sense of. The girls from Montreal were good at mix and match translation. The Argentina - Chile border runs straight down the middle of the Beagle Channel and we had to stay on our side. Port Williams, Chile is about 10 miles east, across the channel, a combination village and naval base. It is Chile’s Antarctic Provincial Capitol and a reminder that they take their borders very seriously. Technically it’s farther south than Ushuaia but not big enough to be a city; with a military and civilian combined population of under 3,000 they don’t argue.

We got a history lesson about HMS Beagle and the discovery of the channel. It’s like Columbus discovering North America; millions of people already living there but he discovered it. The channel was well known to the native population but they didn’t have big boats or need to circumvent the horrible weather farther south. The channel was just big water that went all the way to the other side. The first sea duty for the newly commissioned HMS Beagle was in 1831. At the time, European powers were still jockeying for expansion and control in the Pacific. HMS Beagle, taking the southern route, hugged the coast and explored inlets, finding safe passage that had not been charted before. Like the Straights, unpredictable weather and treacherous currents made it a disappointment. Still, it was another way to the Pacific. Onboard was a newly graduated naturalist, Charles Darwin whose life and times are famously known, an entirely different story.

Ironically, the channel was flanked on both sides by two newly liberated, Catholic nations and their border disputes had been passionately pursued. But the English were the only ones who actually went there and it was Anglican missionaries who settled on the north shore, saving savage souls. We saw the original mission only a few miles into the tour. As good as the stories were, nothing matched the stark isolation, harsh conditions, the interface of icy salt water and sheer mountains. There were several tiny islands, outcroppings where sea lions were hauled out; the air was warmer than the water. The only sea birds were cormorants, big, black diving birds. They were fishing, sharing space on the rocks with sea lions. I had wondered why our hostel was named for them but after watching them work, it seemed natural.

I met a Dutch psychologist, Jos (Yohs). He was nearly my age, traveling alone. We made small talk and agreed to lunch the next day. My young girl friends from Montreal were flying out soon, back to Canada. I hadn’t decided how long to stay. It seemed moot at that point: where else was there to go? As you near the poles, north or south, darkness comes on without much warning. When we saw lights on the waterfront and in town, the sun was still well up above the horizon. By the time we set foot on shore a short half hour later it was pitch dark. Told the girls goodby and Godspeed, confirmed lunch with Jos at La Rueda and cruised San Martin Ave. Cerrado (closed) signs on most doors, bars and cafes still selling but too early for the drinking crowd. But it’s always a good time for an empanada. Some were sweet, others savory and I’d become partial to them: every bakery had them and every street had a bakery. I didn’t ask what was inside, only pointed and paid. I never got a bad one and the surprise inside was worth the suspense.

Across from Los Cormoranes and down the hill was a laundry. Drop off in the morning, ready in the afternoon; I would have clean, dry clothes for a while. So I had things to do early, a lunch appointment and check into a tour of the prison. The French had Devil’s Island, an infamous penal colony from which there was no escape. About the same time, in Argentina, the government wanted a place to send habitual criminals who kept recycling into their jails and prisons. Long story short: repeat offenders were sent to the small community of British missionaries on Beagle Channel and given the task of building their own prison. Like Devil’s Island, even if you escaped, where would you go? As the story goes, the evolution of prison and prisoners set the stage for a Latino culture to take root there and that’s the story I wanted to discover at the prison-museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment